|

| PC: The Nature Conservancy |

Today is the fifth annual World Pangolin Day, and I am struggling to stay optimistic about the future of this unique and incredible animal. There are eight species of pangolin living in Asia and Africa, and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature's Red List considers all of them vulnerable (the four African species) endangered (Indian and Philippine pangolins) or critically endangered (the Chinese and Sunda pangolin). They are virtually resistant to predation in the wild, rolling up into an impenetrable ball of scales than even lion teeth can't break. Unfortunately, thanks to our opposable thumbs, rolling into a ball is not a very useful defense against humans.

|

| PC: Mark Sheridan-Johnson |

I have been sharing information about pangolins for a few years now, and the two most frequent reactions I get are "So cute!" and "So sad!"

There are different ways to deal with the emotions around the latter. Some are healthier than others.

Aggression

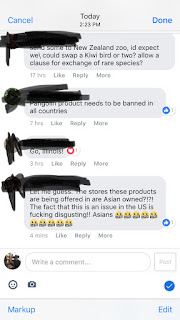

One is blaming the Other. This type of blatant racism is infuriatingly common (and to anyone with a passing familiarity with this thing called the internet, completely unsurprising) on posts (Facebook, Instagram, news articles) related to wildlife trafficking and animal consumption, but also in a less blatant form in journalism and academic literature. With fish and whales it appears to be targeted most strongly at Japan (even though Iceland, Norway, and Denmark are also major whaling nations, and the vast majority of whales were historically killed by *checks notes* the US, UK, and USSR). With terrestrial mammals mainland Asia (especially China) and Africa receive most of the vitriol. The alleged rapaciousness of Asia is one manifestation, which ignores that Europe and the US have long since hunted much of our native wildlife (e.g. the American bison, passenger pigeon, wolves, grizzly bears (whose native range stretched down to Missouri)) into extinction or reduced to small game reserves.

|

| WTF is wrong with people |

What is most insidious about this environmentally-focused racism is that it directly recapitulates the white supremacy and patronizing condescension of imperialism on a post-colonial context that only exists because of imperialism and global capitalism in the first place. Smuggling and poaching networks take advantage of global shipping routes; guns, nets, and traps are often made and sold in the West or by Western companies; and demand itself is often a product of the contingent circumstances of war and empire (I will write a blog post in the future about the rise of whale meat and bluefin tuna in Japan as consumer products - the US occupation post-WWII was a pivotal moment for their adoption and integration into self-reproducing cultural pathways like school lunches. Japan's fishing and whaling fleet was rebuilt using US dollars and State Department guidance).

With pangolins, I am still learning about their cultural roles in their native environments. It isn't particularly helpful that Western media loves to recapitulate the clickbait-y trope that "This obscure animal will go extinct before you even know it exists!" which assumes nobody knows anything about pangolins. In fact, they feature prominently in Southeast Asian mythology, where they travel throughout the world in a vast underground tunnel network, earning them the Cantonese name Chun-shua-cap, or the creature that bores through the mountain.

I think one aspect of this environmental racism is the assumption that because something is happening in a given location, everyone from that location is complicit. This couldn't be more wrong. In particular, it erases the hard work and incredible bravery of educators, park rangers and wildlife rescue workers in places where being an environmentalist can put you on the wrong side of a $20 billion per year organized crime industry. Over five hundred (and potentially up to a thousand) park rangers have been killed in the past ten years alone, many by poachers. They need support, not dismissal.

Nihilism

Another reaction to the wildlife crisis is embracing the void. Earlier this week, a colleague and close friend working on biodiversity issues was asked by a senior scholar in our field why it all matters - wildlife is doomed, the species we care about will go extinct, we humans are headed for a climate-change induced demographic collapse. I've been pondering this nihilistic reaction in my head all week. I think at the end of the day it's a protective mechanism; we shut down and become cynical to avoid having to emotionally process the horror of the world and our complicity in it. One of my favorite scholars, ecofeminist and multi-species ethnographer Donna Haraway, asks in her latest book, Staying With The Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, how we can avoid succumbing to the twin fallacies of techno-optimism (everything will be ok because we have the power to control the universe and fix it) and despair. Her solution is simple but not easy; we have to make connections across boundaries like nation, class, race - and species.

So: how do we make connections?

One way is through education. The more we know, the more we can share with our networks and communities. I am sharing a few articles about the wildlife trade here that get behind the scenes into the business of trafficking and consumption. They are not all perfect in their perspectives, and my sense from traveling briefly in Southeast Asia and talking to people here is that the widespread indifference to wildlife trafficking some of these articles cite is changing rapidly. That said, I think they have something valuable to offer.

In Vietnam, Rampant Wildlife Smuggling Prompts Little Concern

The Most Trafficked Mammal You've Never Heard Of

Sir David Attenborough Picks Ten Animals He Would Take on His Ark

Another way to connect is by supporting organizations that do direct conservation. There are two main ways to do this: top-down hierarchical methods, and grassroots or bottom-up approaches. While both have advantages and disadvantages, I don't think comparison is useful; they're both necessary and fill different niches.

The IUCN's Pangolin Specialist Group is one example of the hierarchical model; it funds work on pangolin conservation biology, which can help create government conservation plans. These are often essential but can be frustratingly slow. Pangolin Conservation is one of the few Western-based environmental organizations dedicated solely to (surprise!) pangolin conservation. They raise money for consortiums of researchers, advocate for laws to crack down on pangolin products sold in the US, and do valuable networking between zoos and other conservation organizations that otherwise might not be in contact with each other. They are also experimenting with captive breeding programs; pangolins are extremely difficult to keep alive in captivity, but some success has been had at local rescue parks in Namibia, Vietnam, and elsewhere. Ex situ conservation is never ideal, but when in situ conservation is struggling, it is an option that requires consideration.

Pangolin Conservation is not by any means big. Local wildlife rescue organizations are often even smaller and even less well funded. They include the locally-run Save Vietnam's Wildlife, which is one of the few organizations that rehabilitates injured pangolins and is frequently at capacity when new pangolins arrive that need help. Their director, Nguyen Van Thai, has had to rush to rescue smuggled animals before corrupt officials sell them back to the black market. There are also programs like REST (Rare and Endangered Species Trust) Namibia and World Land Trust which are not solely dedicated to pangolins but fund park rangers who defend broader habitats against poachers.

If you are interested in doing something to help, I would recommend donating to either Pangolin Conservation or Save Vietnam's Wildlife. I am looking for ways to volunteer - Pangolin Conservation suggests there will be more opportunities in the future. In the meantime, I hope we can stay with the trouble - embrace and lean into our connections, and while not drowning in grief, allow ourselves to feel what we are losing.